Up to this point in this blog, I've only treated stitches that look the same on both sides of the cloth, with one exception: crocheting in the round.

When you crochet or knit [note: knit, not knit and purl] in the round, the bulk of the ruffle yarn remains on one side of the work, creating a tight ruffled texture on one side and the traditional appearance of knitting or crocheting on the other. When you work flat, the yarn stays on the same side of the hook or needles, but each time you turn the work, you alternate working from the front and the back of the garment. This causes the ruffle to appear on both sides of the work, making it difficult to use for many garments other than The Scarf.

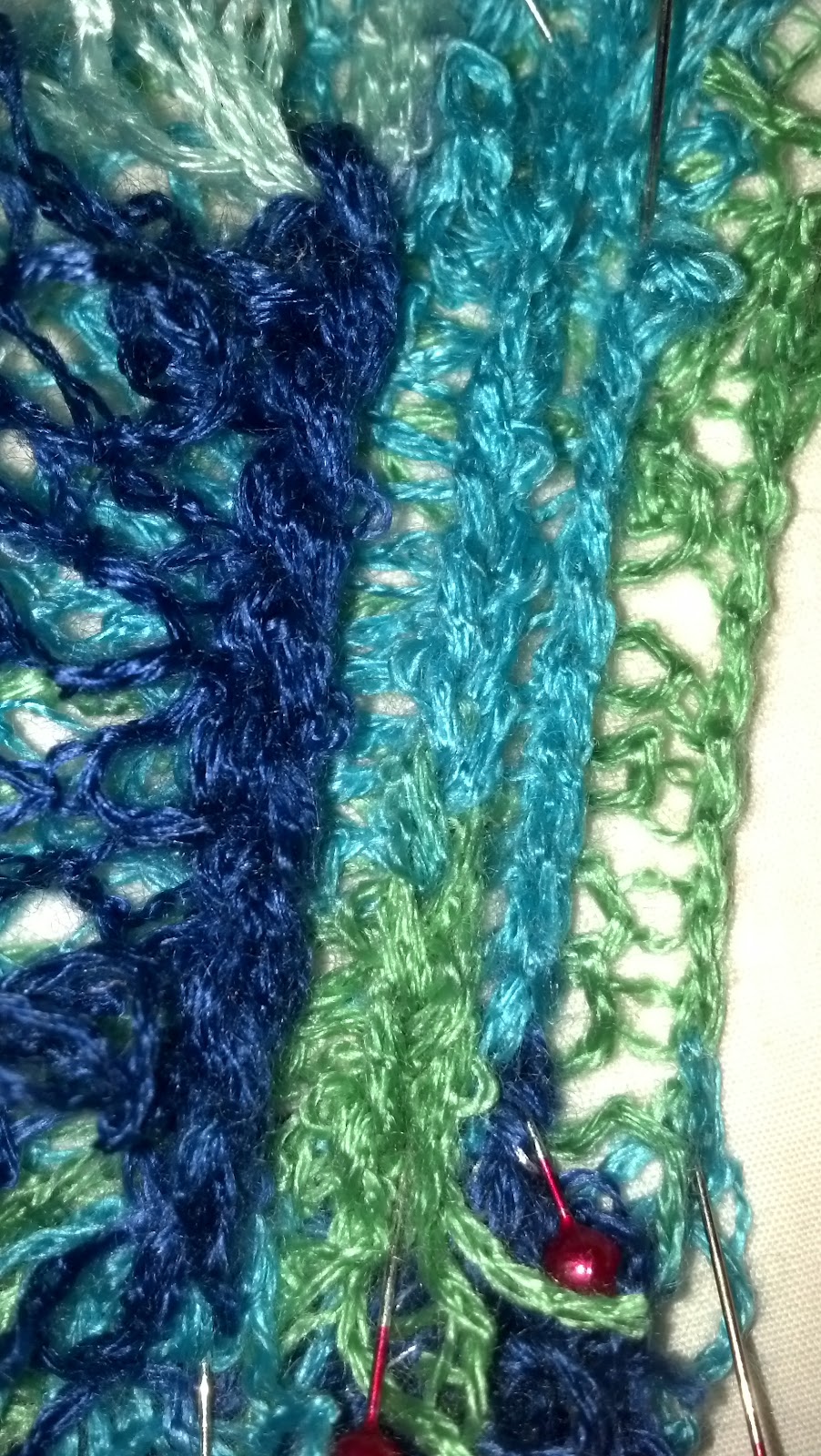

Knitting has a basic stitch that is different from the front and back of the work: stocking (stockinette) stitch. Alternating rows of knit and purl, the structure of the knit is seen on one side of the work, while a more condensed version of the garter stitch appears on the other side. With ruffle yarns, this usually-reverse side will contain all the fabric of the ribbon or mesh, while the knit side will appear as a loosely-worked traditional knit. Viewed from this side, the technique is called reverse stockinette stitch.

Crochet is another matter. In order to get a distinctive front and back of the work, we need to make sure that we are always feeding the yarn from what will become the outside of the finished fabric. Because this means switching the ball of yarn from in back of the work (when the ruffling is facing away from you) to the front of the work (between you and the hook, when the ruffling is facing towards you), I'm referring to it as "Ball Front/Ball Back". The following video describes the technique.